Chagas disease

What is Chagas Disease?

Chagas disease is a parasitic infection caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. It is named after Carlos Chagas, the Brazilian doctor who first diagnosed the disease in 1909.

As with other neglected tropical diseases, the infection can lead to severe chronic complications if diagnosis is delayed and treatment and follow-up are incomplete. In the case of Chagas, complications occur in about 40% of cases, especially at the cardiac and gastrointestinal levels. These are mainly cardiac and gastrointestinal. If not diagnosed and treated in time, Chagas disease can be fatal.

Currently, it is estimated to affect around 7 million people worldwide, with around 12,000 deaths each year. Although it has spread globally due to increased population mobility, it remains most prevalent in 21 countries in the Americas, where the risk of transmission is closely linked to the presence of the insect that transmits it: the triatomines.

Transmission

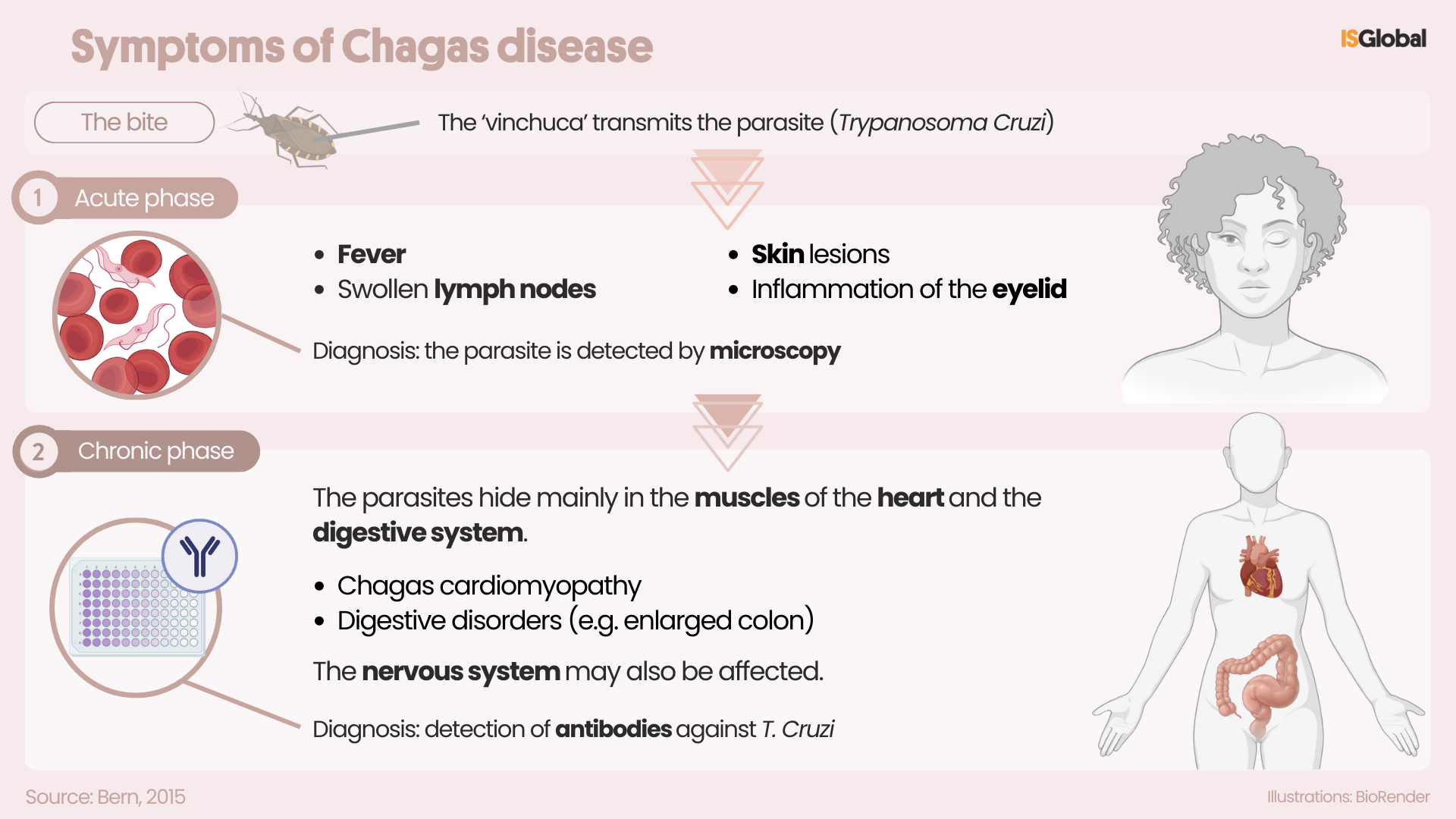

In endemic countries in the Americas, Chagas disease is mainly transmitted by contact with the feces of infected triatomine insects.

A triatomine insect is a large, winged insect (2-3 cm) known as ‘vinchuca’, ‘chinche besucona’ o ‘pito’, depending on the geographical location. They traditionally live in cracks in the walls and roofs of rural houses, where they hide during the day. At night, they bite exposed areas of skin, such as the face. If they defecate near the bite site, the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, which is present in the feces of the triatomine, can enter the body when the person scratches the affected area. The insect is now also found in urban areas and in new environments due to population movements and its adaptation to new habitats.

The parasite can also be transmitted in other ways, such as through the consumption of food that is contaminated with the vector’s faeces, or from mother to child during pregnancy or childbirth. It can also infect pets and other animals that act as natural reservoirs for the parasite. It can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ donations or laboratory accidents.

Symptoms

In the acute phase of the disease, which lasts about two months after infection, symptoms are usually mild or non-specific, such as fever or swollen lymph nodes. In some cases there may be a skin lesion or swelling of the eyelid, but many people show no obvious signs.

In the chronic phase, the parasites hide mainly in the heart muscles and the digestive system. Decades after the infection, up to a third of patients may develop heart problems, such as arrhythmia or heart failure, and about 10% may develop digestive problems, such as enlarged esophagus or colon. In the most severe cases, the disease can cause sudden death due to heart problems or progressive failure due to heart damage. Digestive problems can have a major impact on quality of life, and nervous system involvement is more common in immunosuppressed people.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Chagas disease is based on three aspects: medical assessment, history of exposure to the parasite, and laboratory tests.

Diagnosis in the acute phase:

During the first weeks or months of infection, the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite circulates in large amounts in the blood and can be directly detected through a microscopic examination. Serological tests can also be performed to detect antibodies, which indicate that the immune system is reacting to the parasite. In both cases, diagnostic tests are conducted by blood analysis.

Diagnosis in the chronic phase:

As the infection progresses and becomes chronic, the parasite is no longer easily detectable in blood. At this stage, diagnosis is based on:

- Medical evaluation of symptoms and risk history.

- Serological tests (from blood analysis) to detect antibodies against cruzi. According to the PAHO/WHO diagnostic algorithm, at least two different tests must give a positive result to confirm infection.

* Note: rapid tests appear to work well for screening in rural/low-resource populations.

Treatment

Chagas disease is treated with one of the two available antiparasitic drugs (benznidazole and nifurtimox), which are most effective when administered early in the acute phase. However, they become less effective as the infection progresses and side effects are more common in older people.

Treatment is also recommended in patients with reactivated infection due to immunosuppression and in the early chronic phase, especially in women of childbearing age, to prevent congenital transmission (i.e., from mother to fetus during pregnancy).

In addition to antiparasitic treatment, continuous follow-up is essential to monitor for possible cardiac, digestive, or neurological complications throughout the patient’s life.

Prevention

Chagas disease cannot be eradicated in South America because of the widespread presence of wild animals that act as reservoirs for the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite. For this reason, public health efforts focus on preventing human transmission, ensuring early access to medical care, and providing long-term care for those infected.

There is currently no vaccine against the disease. The most effective strategy is to control vector insects by spraying houses with insecticides and improving housing conditions. Screening of women of childbearing age, as well as blood banks and organ transplants, is also crucial to prevent transmission during these procedures.

Prevention includes the use of mosquito nets and hygienic food handling practices, as well as early detection in newborns of infected mothers. Serological and molecular tests play an essential role in the early detection of the disease.

READ MORE

COLLAPSE

- Breaking the Silence: Increasing awareness, diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease in Bolivia and Paraguay(ISGlobal, 2025)

- Lipid Biomarkers May Improve Management of Chagas Disease(ISGlobal, 2024)

- Theseus in the Labyrinth and the Cure for Chagas Disease(ISGlobal, 2022)

- The Combined Use of Two Rapid Tests is Effective for Accurate Diagnosis of Chronic Chagas Disease in the Field(ISGlobal, 2019)

MULTIMEDIA MATERIAL