HIV

What is HIV?

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus (that is, a virus that uses RNA as its genetic material) that primarily affects the immune system. Specifically, HIV infects and damages CD4+ T lymphocytes, also known as helper T cells. These white blood cells support other cells in carrying out their functions; for example, they activate B lymphocytes so they can produce antibodies.

When HIV encounters its target cells — CD4+ T lymphocytes — it fuses with them and inserts its genetic material. In this way, the virus hijacks the cellular machinery to produce copies of itself (virions), which are released into the bloodstream and infect other cells, repeating the process.

Structure of HIV

HIV is a small but highly complex virus. It is surrounded by an outer envelope with glycoproteins, which act as anchoring points. These glycoproteins allow the virus to attach to and enter the cells it infects.

Inside, HIV contains its genetic material, consisting of RNA and the viral proteins needed for its replication. All of this is protected by the capsid.

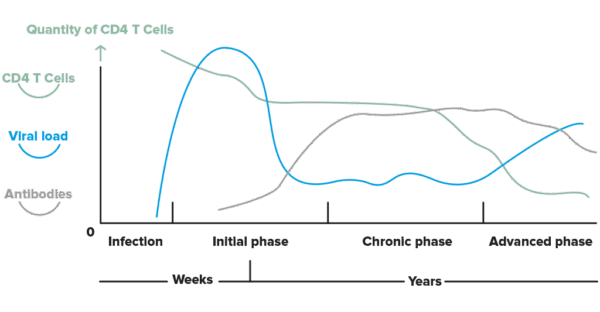

Over time, the number of functional CD4+ cells in the body decreases, leading to an immune deficiency. At the same time, the number of copies of free virus in the blood multiplies exponentially, attacking the body more aggressively. This results in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or advanced HIV disease.

Difference between HIV and AIDS

Living with HIV is not the same as living with AIDS. A person living with HIV may be asymptomatic; the immune system weakens over time, but this does not always result in immediate symptoms or complications.

However, AIDS refers to a set of clinical manifestations that appear when HIV infection is so advanced that the immune system can no longer fight off infections. These are known as opportunistic diseases.

Transmission

HIV is transmitted through contact with body fluids that contain a high viral concentration: blood, breast milk, semen, vaginal secretions… This usually occurs in the absence of treatment or when treatment is failing. The three transmission routes are:

- Sexual. When infected secretions come into contact with the genital, rectal or oral mucosa of another person. This happens during unprotected oral, vaginal or anal sex and in the absence of treatment.

- Blood-borne. In addition to transfusions, HIV can also be transmitted through contact with blood when sharing infected sharp instruments such as syringes for injectable drugs or needles used for piercings or tattoos.

- Perinatal or vertical. HIV can also be transmitted during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding if the mother is not on antiretroviral therapy.

HIV is not transmitted through kissing, saliva, hugging, handshakes, or by sharing personal items or water bottles.

Undetectable means untransmittable. People with HIV who are receiving antiretroviral treatment and have an undetectable viral load do not transmit the virus. Early access to diagnosis and medication, along with good adherence to treatment, is essential for preventing transmission.

Epidemiology

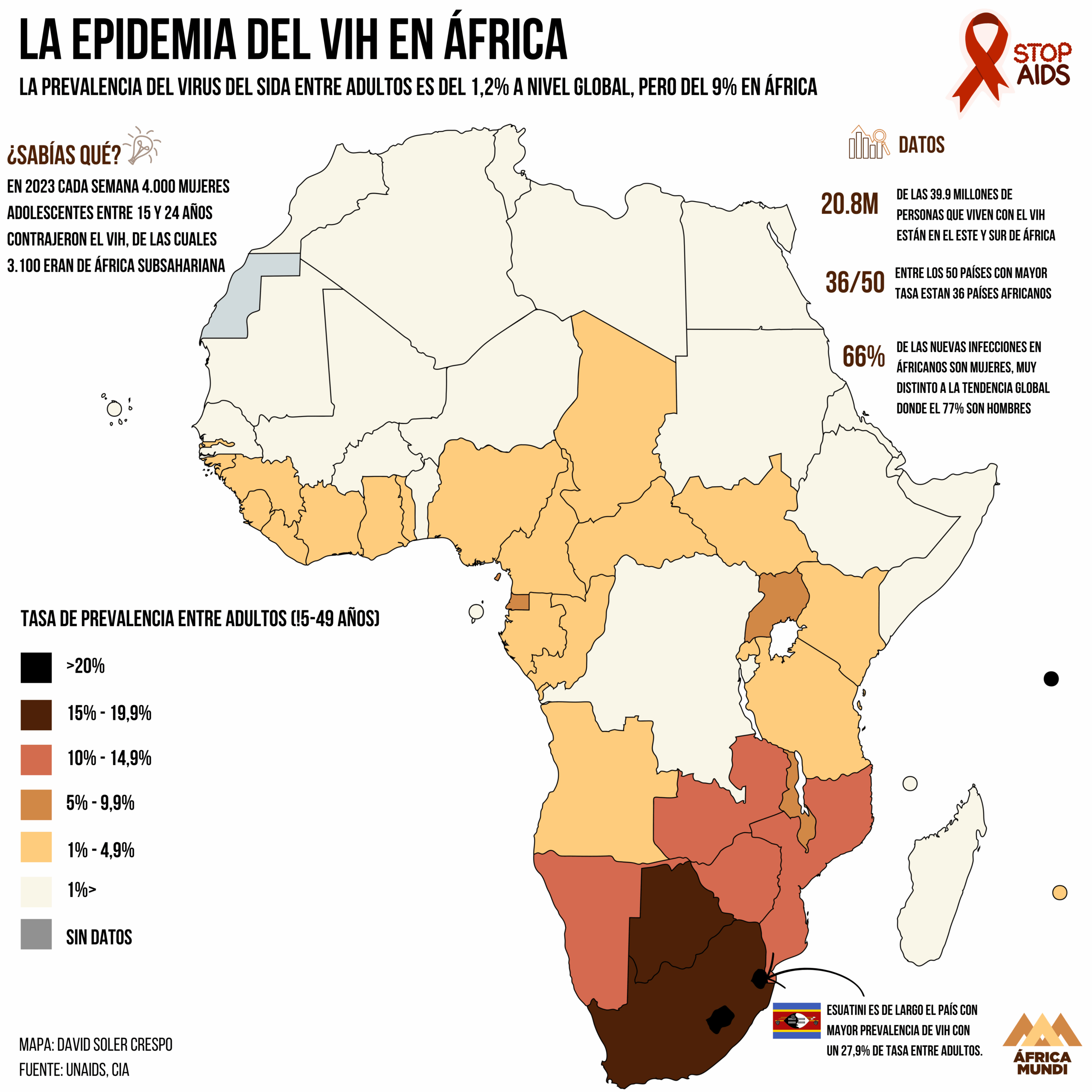

HIV remains a major global public health issue. According to the WHO, in 2024 approximately 630,000 people died from AIDS-related causes. By the end of 2024, there were an estimated 40.8 million people living with HIV and 1.3 million new infections.

The presence of HIV is not uniform across regions; although it has become a manageable chronic condition in much of the world thanks to access to antiretroviral therapy, it remains one of the leading causes of death in low-income countries. The WHO African region is the most affected: 3.1% of adults were living with HIV in 2024, representing two-thirds of all people living with HIV worldwide. In addition, this region accounts for 50% of new HIV infections globally.

Symptoms

In the first weeks after infection (acute phase), some people are asymptomatic. However, others may develop symptoms similar to a “flu-like syndrome”, which can include fever, nausea or diarrhoea.

After the initial symptoms, the chronic phase begins; a period of clinical latency or asymptomatic HIV, which can last for years in adults. However, the immune system progressively weakens due to the decline in CD4+ lymphocytes. Towards the end of this stage, weight loss, persistent diarrhoea or swollen lymph nodes may occur.

Without treatment, HIV infection in adults typically progresses to AIDS within 8 to 10 years, leading to serious health problems that, if untreated, can be fatal. Some of these opportunistic diseases include tuberculosis, cancers (such as lymphomas or Kaposi’s sarcoma), meningitis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C or mpox (monkeypox). However, in children the situation is different: mortality increases to 50% within the first two years of life if they are not diagnosed and treated early.

Diagnosis

There are two types of tests to diagnose HIV infection.

- Serological tests. These detect the body’s response to the virus.

- Antibody tests. These are the traditional tests and detect antibodies against HIV in blood or oral fluids. The immune system produces them after being exposed to the virus, but they may take 6 to 8 weeks to appear in the blood.

- Combined tests. These include 3rd- and 4th-generation tests, capable of detecting antibodies and the p24 antigen simultaneously — a viral protein that appears earlier than antibodies.

Serological tests are rapid tests that can detect antibodies or antigen/antibody combinations in 15–30 minutes. Any positive result requires confirmation.

- Virological tests. These molecular tests (NATs or PCR) directly detect the genetic material of the virus and also allow measurement of the amount of free virus in the blood (viral load). They are used as confirmatory tests after a positive result or to monitor a patient’s response to treatment.

The window period for HIV testing

Right after exposure to the virus, there is a period during which HIV may not be detectable through serological tests. For this reason, if the test result is negative but there has been a recent risk, it is recommended to repeat the test a few weeks later.

In the initial phase of HIV infection, the viral load (the virus’s genetic material) is very high, while antibodies may not yet be detectable. Over time, the number of functional CD4+ cells in the body decreases (immune deficiency). Image: Hospital Clínic de Barcelona

Treatment

HIV treatment is based on antiretroviral drugs, which control the virus by minimising its replication. They are effective, safe and usually taken as a single daily tablet, and thanks to recent discoveries, they may potentially be administered as periodic injections (although this is not yet available as a first-line treatment).

Is there a vaccine for HIV?

A vaccine is the greatest hope for controlling HIV, but it is very difficult to develop due to the virus’s mechanisms for adapting and evading the immune system. However, there are other highly effective and promising methods of prevention.

Prevention

A classic and highly effective measure is the use of condoms, which protect against HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Added to this is avoiding the sharing of objects that may contain blood —syringes, needles, razor blades or toothbrushes— and, in the case of a woman living with HIV, taking treatment and avoiding breastfeeding to prevent transmission to the baby, in addition to giving the newborn a postnatal prophylactic treatment.

Furthermore, these three biomedical strategies have transformed prevention:

- PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis): this is a preventive treatment for people without HIV who are at high risk. Traditionally it is taken as a daily pill.

- Lenacapavir: this is one of the most innovative alternatives within PrEP. It is administered as a long-acting injection every six months, which makes adherence easier. It has shown very high efficacy in preventing HIV and is already part of the recommended strategies in several public health settings in high-income countries. The problem remains its high price and the limited access in places with the greatest infection burden, which tend to be low- and middle-income countries.

- PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis): it is used after a risk situation and must be started as soon as possible to be effective.

Prevention is also supported by treatment; when treated, people living with HIV do not transmit it to others (Undetectable = Untransmittable). For this reason, access to diagnosis, starting treatment as early as possible, and maintaining it consistently are crucial.

Treatment with antiretroviral drugs has significantly reduced AIDS-related deaths, turning HIV into a manageable chronic condition in much of the world. However, it remains one of the main causes of death in low-income countries.

READ MORE

COLLAPSE

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)(ISGlobal)

- Conditional Cash Transfers Significantly Reduce HIV/AIDS Cases and Deaths in Highly Vulnerable Populations(ISGlobal, 2024)

- AIDS statistics(UNAIDS, 2024)

- Let Communities Lead in the Fight to End AIDS(ISGlobal, 2023)

- HIV Care Needs to Focus on Long-Term Well-Being of Patients(ISGlobal, 2023)

- Detail: HIV and AIDS(OMS, 2023)

- Ending the HIV Epidemic by 2030: From Science to Practice(ISGlobal, 2022)

- Improving the Long-term Well-being of People Living with HIV(ISGlobal, 2021)

- A Fungus is Major Cause of Death Among People with HIV in the Brazilian Amazon(ISGlobal, 2021)

- What is HIV?(InfoSIDA)

MULTIMEDIA MATERIAL